A320, vicinity Karachi Pakistan, 2020

A320, vicinity Karachi Pakistan, 2020

Summary

On 22 May 2020, an Airbus A320 made an extremely high speed unstabilised ILS approach to runway 25L at Karachi and did not extend the landing gear for touchdown. It continued along the runway resting on both engines before getting airborne again with the crew announcing their intention to make another approach. Unfortunately, both engines failed due to the damage sustained and the aircraft crashed in a residential area near the airport and was destroyed by impact forces and a post-crash fire. 97 of the 99 occupants died and four persons on the ground were injured with one subsequently dying.

Flight Details

Aircraft

Operator

Type of Flight

Public Transport (Passenger)

Flight Origin

Intended Destination

Take-off Commenced

Yes

Flight Airborne

Yes

Flight Completed

No

Phase of Flight

Missed Approach

Location

Location - Airport

Airport

General

Tag(s)

Approach not stabilised,

Inadequate Aircraft Operator Procedures,

Ineffective Regulatory Oversight

FIRE

Tag(s)

Post Crash Fire

HF

Tag(s)

Authority Gradient,

Inappropriate crew response - skills deficiency,

Inappropriate crew response (automatics),

Ineffective Monitoring,

Manual Handling,

Plan Continuation Bias,

Procedural non compliance,

Stress,

Dual Sidestick Input,

Ineffective Monitoring - SIC as PF,

AP/FD and/or ATHR status awareness

LOC

Tag(s)

AP Status Awareness,

Loss of Engine Power,

Aircraft Flight Path Control Error,

Hard landing,

Collision Damage,

Incorrect Aircraft Configuration,

Aerodynamic Stall

EPR

Tag(s)

MAYDAY declaration

Outcome

Damage or injury

Yes

Aircraft damage

Hull loss

Non-aircraft damage

Yes

Non-occupant Casualties

Yes

Number of Non-occupant Fatalities

1

Occupant Fatalities

Most or all occupants

Number of Occupant Fatalities

97

Off Airport Landing

No

Ditching

No

Causal Factor Group(s)

Group(s)

Aircraft Operation

Air Traffic Management

Safety Recommendation(s)

Group(s)

Aircraft Operation

Air Traffic Management

Airport Management

Investigation Type

Type

Independent

Cite This Page

SKYbrary Aviation Safety. (July 4, 2024). A320, vicinity Karachi Pakistan, 2020. EUROCONTROL.

Retrieved February 1, 2026

from https://skybrary.aero/accidents-and-incidents/a320-vicinity-karachi-pakistan-2020

UID: 20975

Copied!

COPY

Description

On 22 May 2020, an Airbus A320 (AP-BLD) being operated by Pakistan International Airlines on scheduled domestic passenger flight from Lahore to Karachi as PK 8303 touched down on runway 25L at destination in day VMC without the landing gear down. It continued along the runway resting on its engines for almost 700 metres before taking off again but both successively failed soon afterwards due to loss of engine oil and lubrication and when control was lost the aircraft crashed into a residential district approximately 1340 metres from the runway 25L threshold and was destroyed. Only two of the 91 passengers survived and all eight crew were also killed. Four people on the ground were injured, one of which subsequently died. Considerable structural and fire damage occurred where the aircraft crashed.

Investigation

An Investigation was carried out by the Pakistan Aircraft Accident Investigation Board (AAIB). Clearance of wreckage from the crash site prioritised successful recovery of the DFDR and CVR which was achieved and relevant data was successfully downloaded from both recorders by the French BEA. The DFDR recording ceased when both engine AC generators ceased to function but after a short gap whilst automatic RAT deployment occurred, CVR recording continued. ATC voice and radar recordings were the also available as were relevant CCTV recordings. Using these sources, it was possible to reconstruct the flight path with timings accurate to +/- 2 seconds. A Preliminary Report detailing early work of the Investigation was published on 24 June 2020.

The 58 year-old Captain had been employed by the airline for 33 years and had a total of 17,252 hours flying experience of which 4,783 were on type, all in command which he had first gained on the ATR42/72 turboprop fleet five years prior to the accident after 10,208 hours as a First Officer on the Fokker F27, Boeing 737, Airbus A310, and Boeing 777. The 33 year-old First Officer had been employed by the airline for 10 years and had a total of 2,291 hours flying experience of which 1,504 hours were on type after earlier time on the ATR42/72. It was established that a 2019 check of both pilot’s licences had found they had been correctly issued and maintained. The 34 year old APP controller had first qualified as a TWR controller 9 years previously and had one year’s experience in the APP position and the 28 year-old TWR controller had two years' experience as a TWR controller.

What Happened

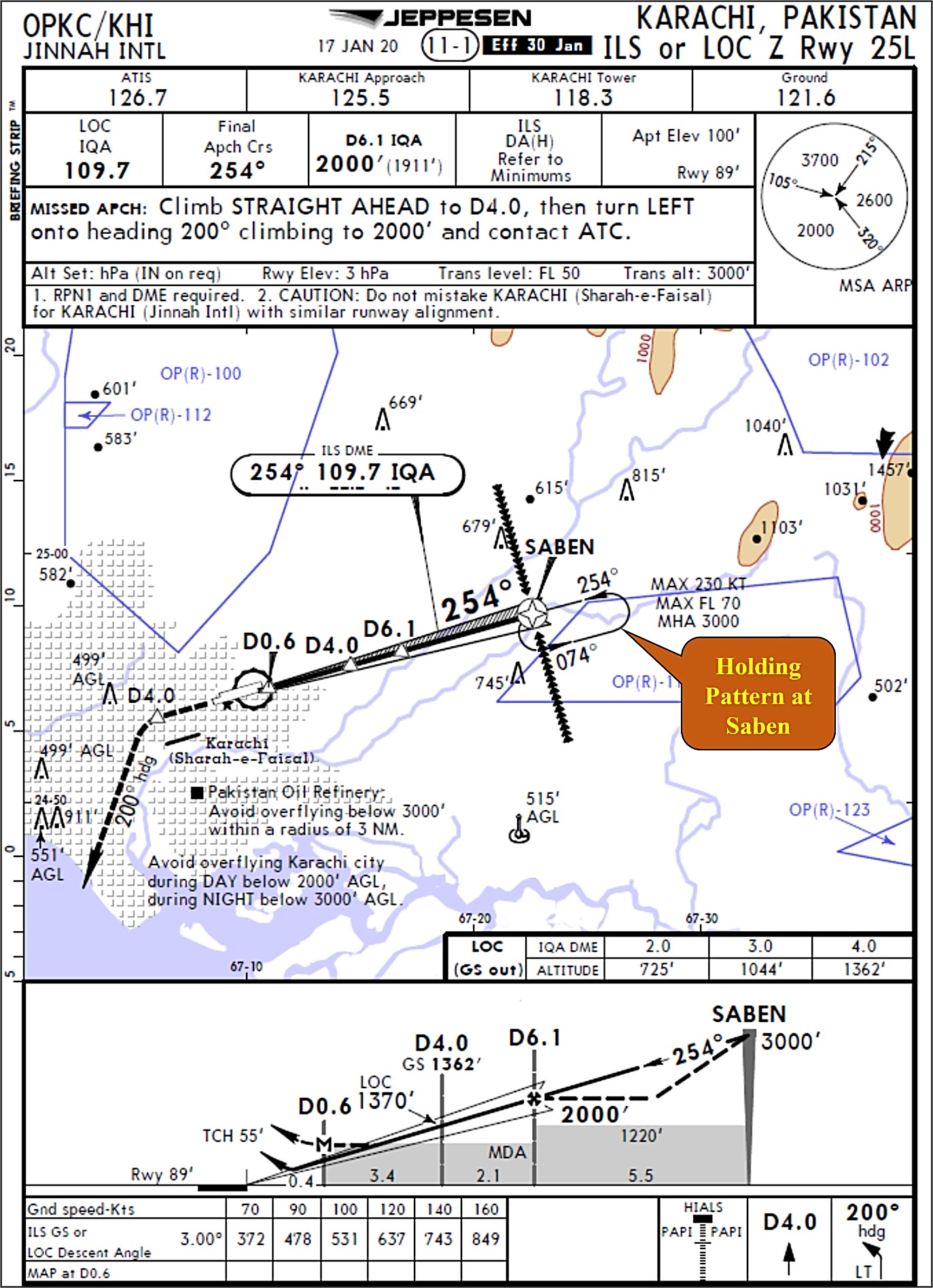

The prevailing weather conditions were noted as having been good throughout the flight which, with the First Officer acting as PF, was uneventful until the descent to Karachi was taking place. Karachi Control cleared the flight for the NH 2A STAR and advised that an ILS approach to runway 25L could be expected. A descent from FL340 was not requested until almost an hour later and when it was, the previous SID clearance was replaced by descent to FL100 and a direct routing to the waypoint MAKLI which is 15.3 nm from the runway 25L threshold close to the SABEN waypoint (see the procedure chart below) which is 11.4 nm from the runway 25L threshold and on the ILS LOC. Descent to FL050 was subsequently given and the AP remained engaged.

The Runway 25L ILS procedure. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

Seven and a half minutes after beginning the descent, Karachi Control instructed the flight to change to Karachi APP but despite several calls and a relay attempt, no response was received. The APP controller also called the flight on the APP frequency but got no response either. Only after three calls on 121.5 was a response received and the transfer to the APP frequency made where descent clearance to 3,000 feet QNH was given and the ILS 25L approach approved.

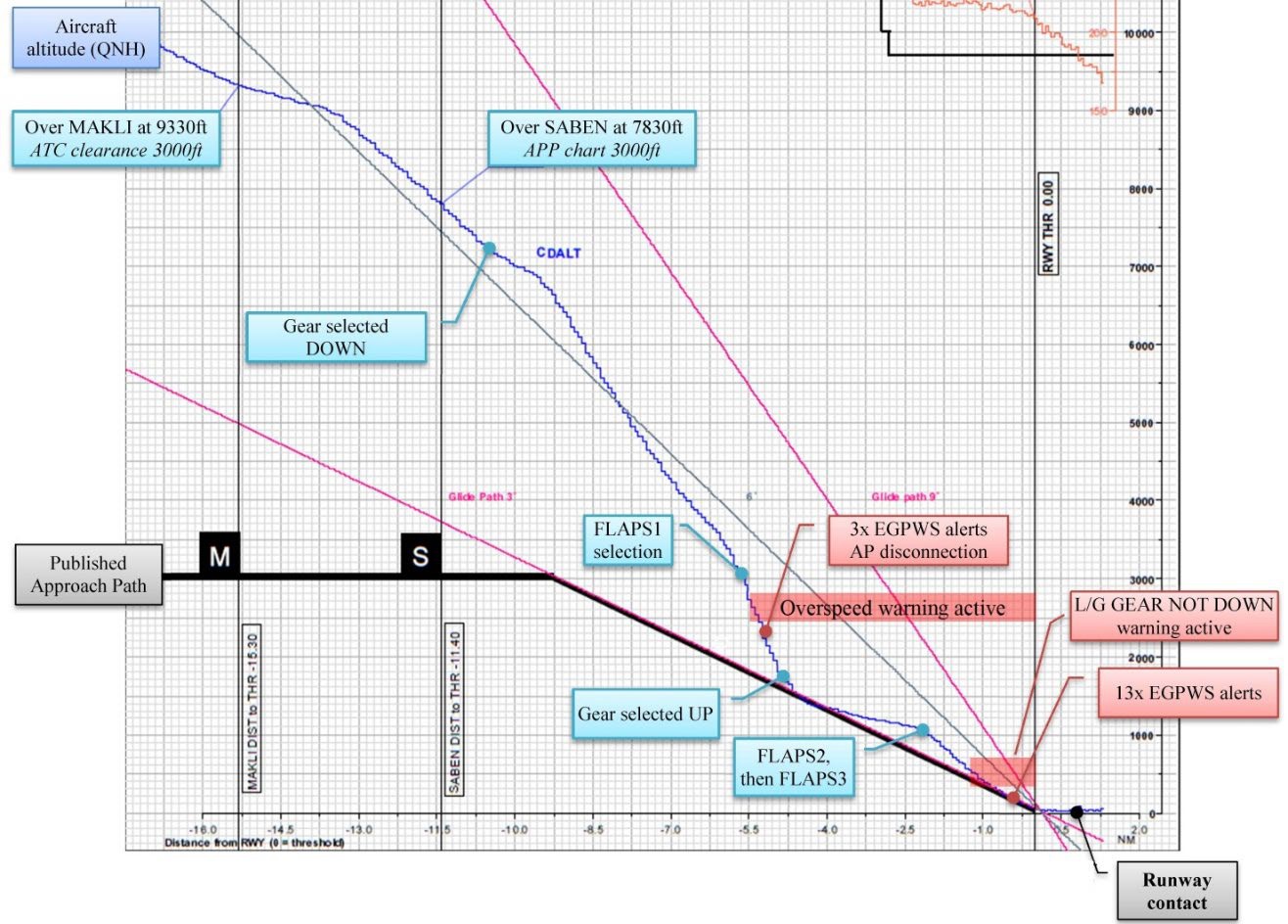

The aircraft remained well above a normal descent profile whilst also maintaining high speed (see the illustration below). On passing MAKLI waypoint, it was still at the equivalent of 9,360 feet QNH and descending at 245 KCAS with the flaps at zero. The controller asked if the flight had sufficient track miles and was assured that it had. Shortly after this, the TWR controller called the APP controller on the hotline expressing concern that the flight was too high and APP controller responded agreeing and saying that he was watching it and would “give an orbit”.

As the flight approached waypoint ‘SABEN’, CVR data included an exchange between the pilots which indicated that the holding pattern at that position used for reducing altitude to 3,000 feet to begin descent on the ILS had been inadvertently left in the FMS and it was removed. The attempt to establish directly on the ILS continued and SABEN, where the ILS GS was at 3000 feet QNH, was overflown at 7,830 feet. The landing gear was then extended after which the rate of descent increased and the APP controller offered an orbit if required but it was declined.

When just under 8 nm from the runway with the rate of descent still over 4,000 fpm, the ILS GS needle had begun to move and the airspeed target was reduced from 248 knots to 230 knots. Having noted the high speed - still over 240 knots - the APP controller twice instructed the flight to “turn left” onto 180° but the Captain declined and responded that they were “established on the ILS 25L”.

With 5.5 nm to go to the runway as an altitude of 3,000 feet was approaching with the speed still 12 knots above the limit for flaps/slats deployment, CONF 1 (flaps/slats) was selected as the ‘OVERSPEED’ warning began to sound and this warning was thereafter continuous. The pitch down was over 12° and increasing and as it reached 13° with a rate of descent of 6,800 fpm, both APs disengaged in accordance with the design of the system. All the visual indications that this had occurred were showing - a flashing Master Warning Red light, an ‘AP OFF’ Red Warning on the ECAM, the AP status disappearing from the flight mode annunciator (FMA) and the light on AP selector going out. However, the only aural alert for this status change - the industry standard “Cavalry Charge” - did not sound because a higher priority was automatically given to the aural ‘OVERSPEED’ continuous repetitive chime.

An EGPWS activation of ‘SINK RATE, PULL UP, PULL UP as the rate of descent reached 7,400 fpm with 5.2 nm to go and the First Officer responded by applying “up to two thirds of full back sidestick for 10 seconds”. This reduced the rate of descent to 5,300 fpm but the speed reached 261 KCAS - 31 knots above the maximum for CONF 1. One second later the landing gear was selected up as the ILS GS was reached. Almost simultaneously, it became clear to the APP controller that the crew intended to continue to a landing despite the highly unstabilised approach being flown. As he was aware that there was no conflicting airborne traffic, he therefore issued the landing clearance which he had earlier obtained by telephone from the TWR controller (who had not mentioned the absence of any extended landing gear).

At 3nm from the runway passing 1,200 feet QNH (the airport elevation is 89 feet) the aircraft, having briefly reached the ILS GS began to deviate above it, the speed reduced below the Overspeed Warning threshold for CONF 1 for two seconds but restarted when CONF 2 was selected at 232 KCAS as this has a lower limit (200 KCAS). CONF 3 selection (Overspeed Warning threshold 189 KCAS) followed almost immediately. At 2.4 nm from the runway and at 1,100 feet QNH, the First Officer was recorded saying “should we do the Orbit?” (in Urdu) to which the Captain replied “No-No”, followed by “Leave it” (both in Urdu). The Captain then took over as PF using his sidestick push button and remained in control until runway contact with the landing gear remaining up.

An annotated vertical profile of the approach. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

As the aircraft passed 750 feet agl, 1.5 nm from the threshold, the speed was 217 KCAS, the rate of descent was 2,100 fpm and the pitch attitude was -5º and the ECAM “L/G GEAR NOT DOWN” message was triggered. An illuminated red arrow appeared next to the Landing Gear selector but there was no change to the aural alerting as the continuous repetitive chime warning of the overspeed condition was still active and no change to the Master Warning flashing red light which was also already active due to the overspeed. The Captain told the First Officer to “cancel it” and the EMER CANC (Emergency Cancel) button on the ECAM Control Panel was pressed which removes the current (overspeed) aural warning for as long as the failure continues and extinguishes the Master Warning Lights. However, this does not affect the ECAM message display or the Landing Gear illuminated red arrow so that both the Overspeed and L/G Not Down messages were still displayed.

At 500 feet agl and 1.2 nm from the runway, the speed was 220 KCAS, the rate of descent 2,000 fpm and the aircraft deviation above the ILS GS was greater than full scale deflection. A second sequence of EGPWS activations began and continued until 24 feet agl. These consisted of ten “TOO LOW TERRAIN” Alerts, one “SINK RATE” Alert and two “PULL UP” Warnings. At 365 feet agl and 0.9 nm from the runway with the speed still well in excess of 215 KCAS, the ‘EMER CANC’ button was pressed again and this stopped the “L/G GEAR NOT DOWN” related continuous repetitive chime, removed the current (landing gear not down) aural warning and extinguished the Master Warning Lights. The conditions for ‘Overspeed’ and ‘Landing Gear Not Down’ were still met so display of these ECAM messages continued.

As the aircraft descended through 30 feet agl at 205 KCAS, the EGPWS activations ceased as per the system design. Both thrust levers were retarded to Flight Idle and at 7 feet agl, still at 200 KCAS, maximum reverse thrust was selected although the reversers did not deploy as the necessary on-ground condition had not been detected.

Five seconds later, the CVR recorded the sound of ground impact which was also verified by reference to the recorded vertical load factor and longitudinal deceleration. Ground markings showed that both engine nacelles were in contact with the runway at about 1,360 metres from the threshold of the 3,400 metre-long runway. This was then intermittently the case for 18 seconds with the right engine remaining in contact with the runway surface for significantly longer than the left. Maximum brake application commenced within two seconds and braking continued as the two pilots made opposite sidestick inputs. The Captain’s inputs were made up to full nose down whilst the First Officer’s were made in the opposite direction up to two thirds of full back sidestick with the resultant elevator position mainly nose down.

Nine seconds after runway contact had begun, full reverse was selected on both engines but the right engine reduced towards idle as an engine fire warning was annunciated for that engine. Fourteen seconds after runway contact had begun, the First Officer said “Take off Sir, Take off” (in Urdu) and two seconds later, at 160 KCAS, braking ceased and the thrust levers were moved to TOGA. Meanwhile, the right engine, which had stalled due to accessory impact damage, began a restart cycle. The aircraft was quickly airborne again as the left engine reached 94% N1. The total length of runway where the aircraft had made intermittent ground contact was found to have been approximately 1,360 metres which meant that the aircraft had taken off again with less than 700 metres of runway ahead.

A “going around” call was made and only then was a full scale emergency declared at the airport. At 59 feet agl, CONF 2 was selected and shortly after this a series of EGPWS Mode 4A Alerts of ‘TOO LOW GEAR’ began and continued until the aircraft climbed to 500 feet agl. Passing 442 feet agl, at 182 KCAS twenty five seconds after becoming airborne again, the N1 on both engines reached 94% and the flaps/slats were fully retracted. However, the recorded left engine oil quantity then dropped quickly from 16 quarts to 4 quarts and that for the right engine dropped from 15 quarts to 5 quarts which was subsequently attributed to damage whilst in contact with the runway. When still below 1,000 feet agl the recorded maximum vibration indication for both left and right engines changed to “non computed data” and eight seconds later, the left engine ‘OIL LOW PRESSURE’ warning was annunciated and was followed by the same indication for the right engine as both engine N1s reduced to 40%. Both warnings continued until end of the DFDR recording.

At 2,160 feet agl, AP1 was engaged and remained so until the end of the DFDR recording. The flight requested radar headings back to the ILS for runway 25L and was given a left turn onto 110° and a climb to 3,000 feet QNH. Shortly after the left turn had been commenced, an un-commanded shutdown of the left engine occurred but the right engine continued at 82% N1.The (PM) First Officer was recorded on the CVR saying “thrust lever number two idle, move number two to idle" (in Urdu) and this movement was made at 3,100 feet whilst the left engine thrust lever remained set to ‘Maximum Climb’ (MCL). From this point, the DFDR recording ceased because both engine AC generators were no was no longer functioning although after an 8 second break in CVR recording until automatic deployment of the RAT had occurred, after which it was re-powered. Radar data showed that the aircraft descended to and then maintained just under 2,000 feet QNH on the heading given for almost a minute but that height had then begun to be slowly lost, although ground speed was maintained at around 220 knots. The pilots then had “a short discussion” about the status of the right engine and having confirmed that it was still running, its thrust lever was moved forwards and around 76 % N1 was achieved. Twenty seconds later, the Captain said that “you had selected engine No. 2 to idle, whereas engine No. 1 was gone” (in Urdu) to which First Officer replied “yes” (in Urdu).

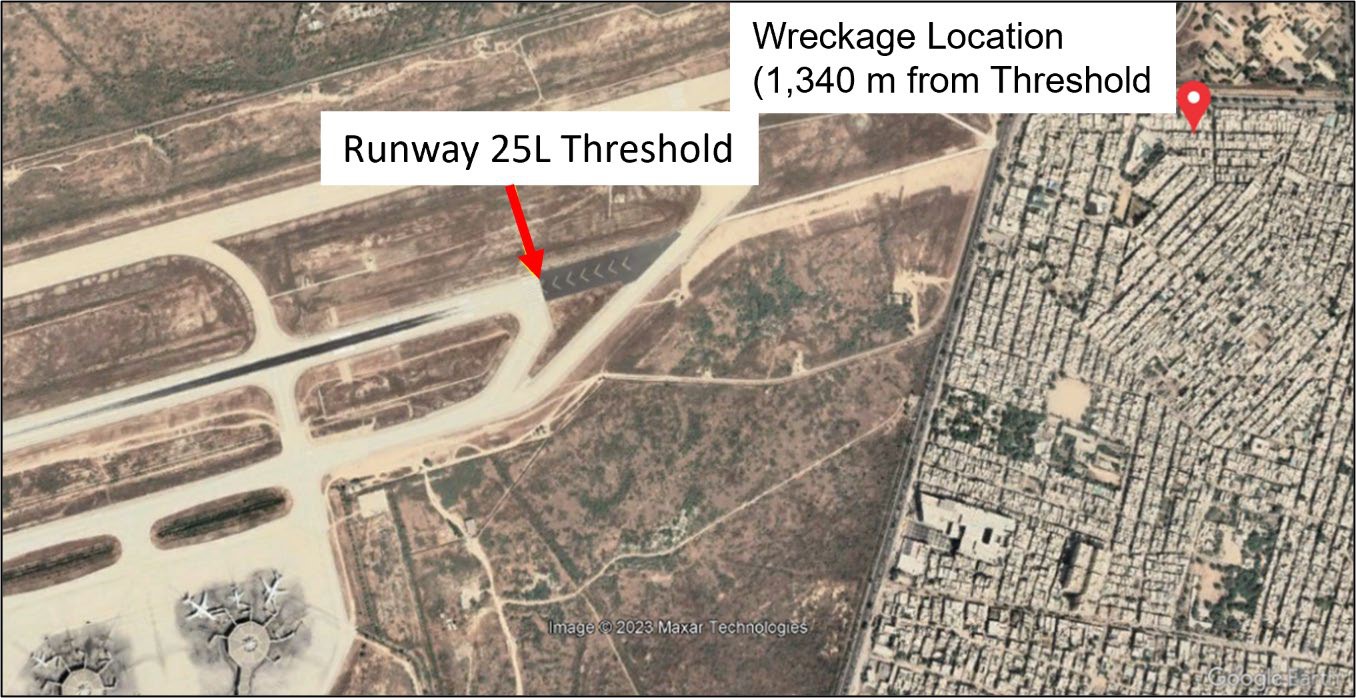

Fifteen seconds after that, noises similar to the right engine stalling were recorded and the right engine N1 briefly fluctuated between 65% and 72% five seconds later, before reducing again and maintaining 65% for just under 30 seconds before running down. A series of Stall Warnings were recorded on the CVR and the First Officer called APP advising that “we will be proceeding direct sir, we have lost engines”. As per radar data, the aircraft altitude was 1,500 feet QNH as it turned left through 004° at a ground speed of 177 knots. A noise similar to the gear extension was heard on the CVR as the left turn continued as height decreased and ten seconds later, a MAYDAY call was made as a sequence of flight deck “stall” annunciations were audible. ATC called to confirm that both runways were available for landing and the Captain said “don’t take flaps” twice (in Urdu). The final radar data showed that the aircraft was at 400 feet QNH at ground speed of 142 knots and turning left through 285°. The aircraft was then seen at a high angle of attack before impact at a low forward speed with the landing gear extended. The CVR recording continued until ending with a sound similar to aircraft impact. The impact site was in a built up area very close to the extended centreline of runway 25L and 1,340 metres from its threshold (see below). A post impact fire began at the point of impact and the remainder of the wreckage was spread over approximately 80 metres, essentially aligned along a single street - see the second illustration below.

The accident site in relation to the runway 25L threshold. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

The crash site along a single street in the Model Colony District - the initial impact point is on the right. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

Why It Happened

The Investigation examined the evidence in detail and concluded that the origin of the accident was the failure of the flight crew to properly manage a routine descent into a familiar airport. When this fact became obvious they then failed to act professionally to prevent avoidable further risk by overloading themselves as they tried continually to recover the situation rather than break off the approach themselves or accept the opportunities to do so offered by ATC.

It was noted that the mismanagement of the descent by the PF First Officer had not been challenged by the Captain and that he had delayed taking over until the only safe option was a go around and then failed to do this. The Captain in particular appeared to have had “no mental picture of the flight path even after being prompted by ATC (lack of situation awareness)” and had led the First Officer by “verbalising that situation was under control (human performance: overconfidence and complacency)”.

It was found that the Captain, who by definition had borne the main responsibility for the safe conduct of the flight had, with hindsight, perhaps not been of suitable character to operate with a junior co-pilot. It was noted that he had been described after examination by a psychologist when inducted into the airline as being “of a bossy nature, firm, dominant and overbearing (with) a tendency to have little regard for the authority” and to have “low comprehension of the mechanical / space relationship and an inadequate level of stress tolerance”. In respect of significant specific errors, the primary one - the retraction of the landing gear and the failure of either pilot to subsequently notice this status - could not be explained except as the apparent result of task overload.

In terms of the teamwork between the two pilots, it was noted that an analysis of flight crew actions, the aircraft trajectory, and the conversation recorded on the CVR had “highlighted an inadequate level of CRM” on the part of both pilots. It was also suspected that the judgment of both pilots had been “probably impaired due to effects of fasting while flying” given that the flight took place during the daytime in the month of Ramadan. However any consequence of this in respect of their performance “could not be determined”.

Three Primary Causes of the Accident were identified as follows:

- The aircraft made a gear-up landing and both engine nacelles made contact with the runway. Both engines were damaged causing loss of engine oil and lubrication which resulted in failure of both engines whilst positioning for a second approach.

- Non-adherence to SOPs and disregard of ATC instructions during the accident flight.

- Lack of communication between the ATC and the flight crew regarding the gear up landing particularly once aircraft was on the runway.

Four Contributory Factors were also identified as:

- Ineffective implementation of Flight Data Analysis programme.

- The regulatory oversight of the operator’s FDA Programme was ineffective in producing adequate and timely improvement.

- The lack of clear and precise regulations in respect of flying whilst fasting.

- The inadequate level of CRM during the accident flight.

A total of 12 Safety Recommendations were made as a result of the findings of the Investigation:

- that Pakistan International Airlines take the necessary measures to ensure compliance with Standard Operating Procedures by flight crew and the effective implementation of the Flight Data Analysis Programme and its integration into Safety Management System.

- that Pakistan International Airlines review its Crew Resource Management programme to promote effective Flight Deck Communication.

- that Pakistan International Airlines take necessary measures to ensure compliance with Regulations regarding the Pre-Flight Medical Check and flying while Fasting.

- that Pakistan International Airlines ensure that all Emergency Locator Transmitters (ELTs) are registered with the State Space & Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO).

- that Pakistan International Airlines shall specify the minimum duration of the meal opportunity and the time frames in which a regular meal should be consumed by flight crew during flight in the Operations Manual.

- that the Pakistan CAA take necessary measures to ensure compliance by both Air Traffic Controllers and Pilots with Standard Operating Procedures.

- that the Pakistan CAA develop an effective Flight Data Analysis and Crew Resource Management regulatory oversight programme.

- that the Pakistan CAA review its existing regulations pertaining to flight crew flying while Fasting and ensure uniform instructions appear in ANOs and CARs 1994 etc.

- that the Pakistan CAA ensure effective regulatory oversight of Pre-Flight Medical Checks including flying while Fasting.

- that the Pakistan CAA require Operators to include the minimum duration of the meal opportunity and the time frames in which a regular meal should be consumed by flight crew during flight are specified in the Operations Manual.

- that the Pakistan CAA devise a mechanism to educate and equip response personnel involved in Search and Rescue Operations for hazards at aircraft accident sites as per ICAO Circular 31 and also take appropriate measures to ensure awareness of this matter at other agencies responsible for Search and Rescue Operations.

- that the Pakistan CAA devise a mechanism to educate response personnel involved in Search and Rescue Operation for evidence preservation.

The Final Report was completed on 20 April 2023 but only released in a “Public Version” online in February 2024.

Related Articles

- Loss of Control

- Stabilised Approach

- Post Crash Fires

- Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

- Crew Resource Management

- Pilot Workload

- Complacency

- Situation Awareness

- Instrument Landing System (ILS)

- Energy Management during Approach

- Landing Gear

- Landing Gear Problems: Guidance for Controllers

- Flight Data Analysis

- Safety Management System