A321, en-route, near Luton UK, 2023

A321, en-route, near Luton UK, 2023

Summary

On 4 October 2023, an Airbus A321 climbing out of London Stansted with the eighteen occupants all seated towards the front of the passenger cabin was discovered to have several missing or damaged windowpanes on the left side towards the rear. The aircraft returned to land where damage was also found to one of the horizontal stabilisers. The window panes fell out because of damage by infrared energy emitted from high-intensity lights during a filming event the previous day. Four previous similar events were identified but it was found that knowledge of them was not widespread in the aviation community.

Flight Details

Aircraft

Operator

Type of Flight

Public Transport (Non Revenue)

Flight Origin

Intended Destination

Actual Destination

Take-off Commenced

Yes

Flight Airborne

Yes

Flight Completed

Yes

Phase of Flight

Climb

Location

Approx.

near Luton

General

Tag(s)

Air Turnback

LOC

Tag(s)

Airframe Structural Failure

AW

System(s)

Airframe

Contributor(s)

Component Fault in service,

In flight separation of failed component

Outcome

Damage or injury

Yes

Aircraft damage

Minor

Non-aircraft damage

No

Non-occupant Casualties

No

Off Airport Landing

No

Ditching

No

Causal Factor Group(s)

Group(s)

Aircraft Technical

Safety Recommendation(s)

Group(s)

None Made

Investigation Type

Type

Independent

Cite This Page

SKYbrary Aviation Safety. (October 2, 2024). A321, en-route, near Luton UK, 2023 . EUROCONTROL.

Retrieved February 2, 2026

from https://skybrary.aero/accidents-and-incidents/a321-en-route-near-luton-uk-2023

UID: 35048

Copied!

COPY

Description

On 4 October 2023, it was discovered during the climb that an Airbus A321 (G-OATW) being operated by Titan Airways on a very lightly-loaded positioning flight from London Stansted to Orlando that several windows towards the rear of the passenger cabin were missing or damaged. A return for an overweight landing followed where an external inspection also found impact damage to the lower surface of the left hand horizontal stabiliser.

Investigation

A Field Investigation into the event was carried by the UK Air Accident Investigation Branch (AAIB). Relevant recorded data was recovered from the FDR and the CVR. It was noted that the 54 year-old Captain had a total of 4,905 hours flying experience which included 2,300 hours on type and was accompanied by two other pilots, one of whom was acting as PF for the departure and climb. The FDR and CVR were removed from the aircraft and their relevant data were successfully downloaded.

In addition to the three pilots, an engineer, a loadmaster and six cabin crew were on board as were nine passengers who were seated together in the middle of the cabin just forward of the overwing exits. The purpose of the flight was to facilitate a multi-sector charter away from the operator’s base which would last several weeks.

What Happened

The Captain’s external pre flight check did not identify anything untoward and at the same time, several company engineers were carrying out a Daily Check and pre departure ETOPS inspections.

Takeoff from runway 22 was normal but several of the passengers subsequently recalled that after takeoff “the aircraft cabin seemed noisier and colder than they were used to”. Passing FL100, the seatbelt signs were switched off and the loadmaster left his seat just in front of the other passengers and walked towards the rear of the aircraft. As he did so, he noticed increased cabin noise as he approached the overwing exits and saw that one of the cabin windows on the left hand side of the aircraft appeared to have slipped down leaving its seal flapping in the airflow. He described the cabin noise as having been ‘loud enough to damage your hearing’.

He briefed the cabin crew accordingly and then proceeded to the flight deck to inform the Captain. At this point, the aircraft was climbing through FL130 and the aircraft pressurisation system was operating normally. The climb was stopped at FL145, the airspeed was reduced and the engineer and the third pilot went to look at the window after which it was agreed that the aircraft would return to Stansted. The cabin was quickly secured and a descent was initially made to FL100 and then continued to FL 090. A holding pattern was flown whilst the overweight landing checklist and an approach briefing were completed. The Captain took over as PF and an uneventful approach and landing to runway 22 followed after 36 minutes. airborne.

Once the aircraft had reached its assigned parking position and been shut down and the passengers disembarked, the pilots inspected the aircraft externally and saw that

two cabin adjacent window assemblies were missing altogether and the ones either side had displaced and/or missing windowpanes and seals. A shattered inner windowpane was subsequently recovered from the entrance to a RET during a routine runway inspection after the aircraft had landed. Since the aircraft had not passed the location where it was found during the landing roll, this windowpane must have separated during takeoff. Further checks of the relevant paved surfaces and adjacent grass did not find any other window assembly components so other found to be missing must have been lost whilst airborne. Those missing parts not recovered included the outer panes from both missing window assemblies but their corresponding inner panes (including the shattered one ejected during departure) were recovered.

An external inspection of the airframe then found that the lower surface of the left horizontal stabiliser leading-edge panel had been punctured and when the leading-edge panel was removed, small pieces of acrylic material were found inside it.

Why It Happened

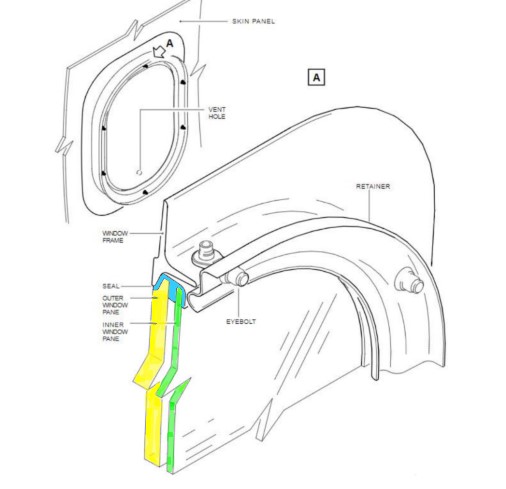

It was noted that each cabin window assembly consisted of two windowpanes which fitted into slots in the rubber seal to form a ‘dry’ assembly (i.e. no adhesives or sealants are used). Each window assembly was then held in compression against the window frame by a metal retainer secured by six eyebolts and nuts (see the illustration below).

The construction of the cabin window assembly showing the two panes and the rubber seal. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

A vent hole through the inner pane allows cabin pressure into the space between the inner and outer panes both of which are individually capable of taking the full differential pressure load if one should fail in flight. An inner ‘scratch panel’ not shown in the illustration is attached to the cabin trim and protects the inner windowpane from damage but this is not part of the load bearing structure. The two windowpanes are made of stretched acrylic which requires cast acrylic to be heat soaked close to its softening point whilst it is stretched into its finished shape to meet the applicable performance specification.

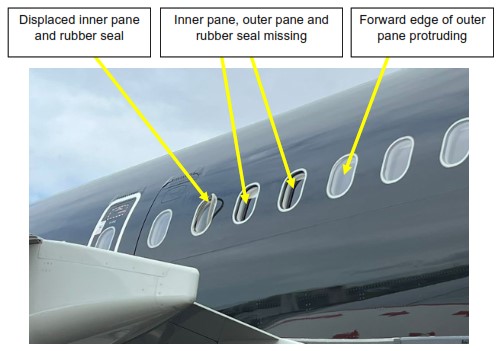

The scratch pane of all four windows was still in position so that there was no “direct unrestricted aperture” into the passenger cabin. One of the two window assemblies that had not been lost had a displaced but partially retained inner pane and seal and the rear part of the outer pane of the other was protruding from the fuselage frame.

Displaced and missing windowpanes on the left side of the aircraft. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

A comparison of the dimensions of serviceable inner windowpanes with those of the two ejected but recovered ones found that the height and width of the latter were respectively of the order of 7% and 6% less than the same measurements for a serviceable windowpane. This was an indication that the windowpanes had been vulnerable to a temperature rise from the film lighting which was beyond their design specification for thermal relaxation. The lighting involved was found to have been six halogen lights with a combined lighting capacity of 72,000 watts which had been sited between 6 and 9 metres from the six windows immediately to the rear of the left hand side overwing emergency exit and had been switched on for four hours. The same lights had also been used to illuminate the right hand side of the aircraft and although they had been on for longer - five and a half hours - they had been directed over a larger area of the fuselage and sited slightly further away from it.

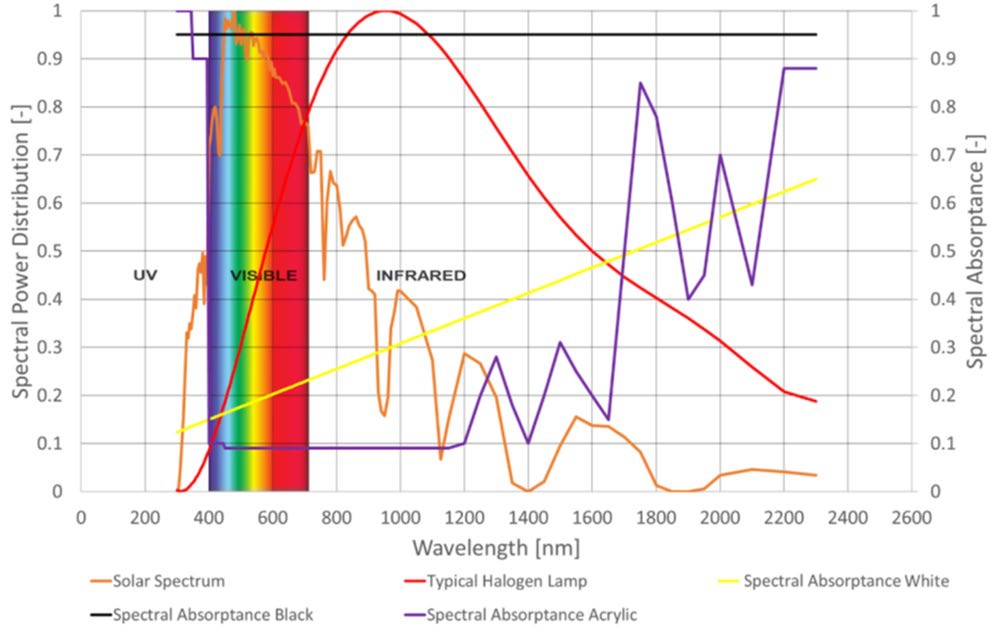

The Investigation was able to obtain (from Airbus) a typical spectral power distribution for a halogen bulb compared to that for solar energy received at the earth’s surface (see the illustration below). This showed that most of the energy from a halogen bulb is in the infrared (IR) zone whereas solar energy is filtered by the atmosphere, dust and humidity and mostly arrives at lower altitudes within the visible spectrum.

Spectral power distributions and material absorptivity. [Reproduced from the Official Report]

It was noted that the amount of heat absorbed by any material is proportional to its absorptivity and increases with increasing wavelength. As shown, acrylic material such as the aircraft windowpanes transmits most visible wavelengths but becomes significantly more absorbent in the IR spectrum. This explains why acrylic (and white painted) structures remain relatively cool in sunlight whereas black coloured structures become hotter. Since the thermal conductivity of a material determines how effectively it can conduct - and therefore dissipate - heat and acrylic has a particularly low such conductivity (600 times less than that for aluminium alloy), it was concluded that the vulnerability of aircraft window integrity to an exposure not provided for in the design specification indicates the need for extreme caution in the use of film lighting to illuminate aircraft. It was considered likely that this matter appeared not to have previously been very widely recognised.

Other Similar Events

The Investigation was able to identify several previous events where acrylic cabin windows had been damaged by high temperatures during filming when high-intensity lights had been used. In all these cases, because the aircraft involved was not about to be operated and the damage was identified and repaired before it was operated there was no obligation to report an accident or a serious incident.

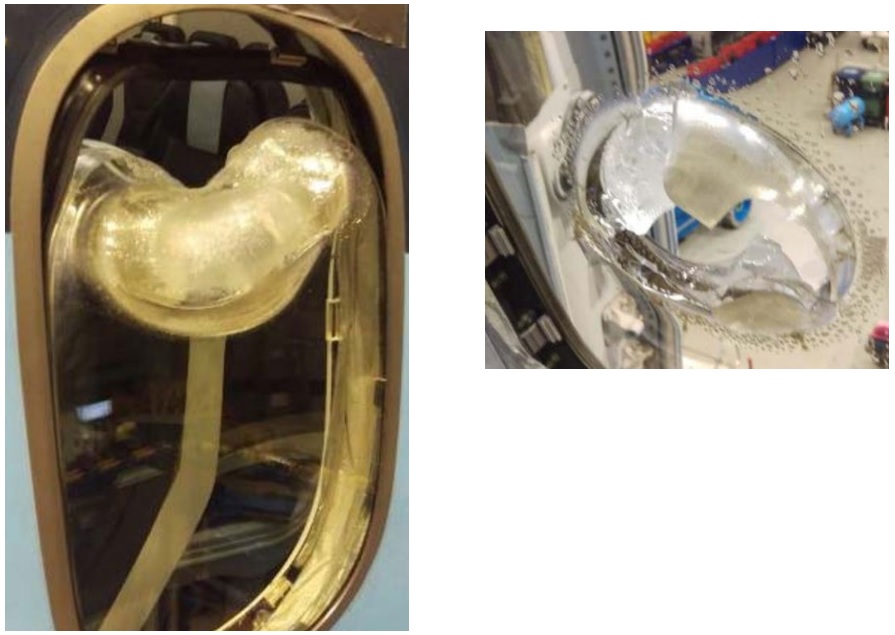

In one case, an Airbus A321 had sustained clearly visible cabin window damage during a filming event when the aircraft was outdoors and spotlights were positioned just inboard of the engines between 1.5 metres and 1.8 metres from the cabin windows. In another, six cabin windows on a Boeing 787 were illuminated by three 2,000 watt lights mounted on mobile platforms outside the aircraft and again were visibly damaged (see the illustrations below). Since three of these previous events had involved Boeing 787 aircraft, Boeing had issued a Fleet Team Digest article on the risk of damage by the absorption of Infra Red energy from high intensity lights.

Two of the Boeing 787 windows damaged by 2,000 watt lights mounted on mobile platforms. [Reproduced from the Official Report where they were used with permission]

None of the other aircraft operators consulted informally about the risk of damage from film lighting during the Investigation had foreseen the risk of airworthiness-related as opposed to cosmetic damage when their aircraft were used for filming or appreciated the complete absence of any appreciation of the potential extent of the aircraft damage risk on the part of the film crews. Whilst aircraft operators’ own maintenance personnel would typically be in attendance, they would have no knowledge of when lighting being used might be capable of damaging an aircraft.

The Investigation found that in effect, the safety management of filming appeared to be largely confined to concern for the health and safety of personnel on site and routinely appeared to take little or no account of lighting equipment datasheets with the technical oversight of film lighting operations being simply a matter of achieving the effects required by the on-site film director.

The Conclusion of the Investigation was documented as follows:

Several cabin window components were lost during the flight. High-intensity lights that were used during a filming event emitted sufficient Infra Red radiation to heat the acrylic windows to a temperature sufficient to soften them leading to distortion and shrinkage. The distorted windows fell out because of vibration or the pressure differential across them as the aircraft climbed after takeoff. The aircraft returned to the departure airport for an uneventful landing.

Safety Action was noted to have been taken as follows:

- Titan Airways reminded its department responsible for the filming of the need to use the risk assessment process for activities like this.

- Airbus published an In Service Information document to highlight the potential adverse effects of using high-intensity lighting near an aircraft.

- Airbus published a ‘Safety First’ article highlighting the possible adverse effects of using high-intensity lighting near an aircraft.

- The European Union Aviation Safety Agency published a Safety Information Bulletin highlighting the risk of damage when using high-intensity lighting near an aircraft.

The Final Report of the Investigation was published on 18 April 2024. No Safety Recommendations were made.

Related Articles

Further Reading

- Under the Spotlights, Airbus Safety First, Feb 2024

- EASA SIB 2024-04: Risks from using high power lights close to aircraft structures, EASA, 6 March 2024